Wind farm planning

I have several articles at various stages of completion, but I could not resist commenting on the flurry of publicity linked to a DESNZ press release concerning planning procedures for onshore wind farms. As background, I was a member of the Infrastructure Planning Commission (IPC) in the early 2010s. The IPC was established in 2009 by the 1997-2010 Labour Government to handle planning applications for what were called Nationally Significant Infrastructure projects. Such projects included all power plants (including wind farms) of at least 50 MW. The 2010-15 Conservative-Liberal coalition merged the IPC with the Planning Inspectorate National Service (PINS) in 2012 but many of the changes in process were retained. In the usual way of UK governments, the new Labour government wants to re-invent the wheel under a new guise.

The current government’s policies concerning renewable energy and Net Zero are a source of comedy that never stops giving. The latest round is an announcement given widespread publicity on Friday December 13th. DESNZ says that it will transfer responsibility for planning decisions for large (100 MW or greater) onshore wind farms away from local authorities to the unit within the Planning Inspectorate National Service (PINS) which deals with Nationally Significant Infrastructure. Planning decisions for offshore wind farms are already handled by this unit. In all such cases the final decision is made by the Secretary of State once the Department has received a recommendation from PINS.

This is largely a reversion to the arrangements in place at beginning of the 2010s. It can be seen as a power grab by DESNZ by transferring the power of decisions from local authorities to the Department. The Secretary of State has always had to power to “call in” any decision of national significance, thus transferring ultimate decision-making power to the Department. All the change does is to (marginally) speed up the planning process.

More important, the announcement is little more than PR spin put out by DESNZ for gullible journalists. Planning matters, including responsibility for power plants and other energy infrastructure, are a devolved matter. The Scottish Government has a unit called the Energy Consents Unit (ECU) of the Division of Planning and Environmental Appeals (DPEA) which has managed all such planning applications since well before devolution in 1997. Scotland accounts for more than 90% by capacity of all onshore wind farm consents over the last decade. Outside Scotland there have been applications for four wind farms of greater than 100 MW in Wales and one in Northern Ireland over the last 20 years but none in England.

It is possible that potential applications for large wind farms in England have been discouraged by the frequent hostility of local residents to large onshore wind farms. However, it is naïve to think that such hostility can easily be overcome if planning responsibility is transferred from local authorities to a central agency. The ECU in Scotland is hard pressed to manage the volume of applications for onshore wind farms that it is expected to handle. Local opposition often forces ECU to hold public inquiries. Even if a Reporter (the equivalent of an Inspector in England) recommends the grant of planning consent this can be challenged and overturned via a judicial review.

If DESNZ genuinely believes that transferring responsibility for planning applications will greatly speed up the planning process or alter the ultimate decisions, their knowledge of what happens in Scotland is sadly deficient. In any case, large parts of England are either unsuitable for onshore wind farms on this scale or they would have to be built in National Parks or Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs) which would create a political firestorm.

Developers today wish to use turbines with a capacity of 4 to 5 MW and a tip height of close to 200 metres. To minimise what are called wake effects, i.e. downwind turbulence which reduces output from neighbouring units, turbines should be sited with 6 to 8 times tip height between units. That means that each turbine will occupy an area of roughly 2 square kilometres. Allowing for margins on the edge of the wind farm, how many areas in England have up to 60 sq.km with good wind resources and no inhabited buildings?

Limits on noise exposure mean that a developer is likely to have to buy any house that is within 1 or even 1.5 km of a turbine. Most of the English countryside, outside designated areas like Dartmoor and the North Yorkshire Moors, has population densities that are too high to be suitable for large wind farms. Thus, the number of proposed wind farms that will be affected by the DESNZ proposal is tiny.

Even though DESNZ appears not to understand who is responsible for making planning decisions on offshore wind projects, there is a larger issue which it ignores entirely. Suppose that a few more onshore wind projects obtain planning consent. Will any of these projects actually be built? Recent suggests that most of them will remain in limbo: the consents will blight the lives of anyone living close to the development but no ground will be broken and no wind turbines will produce any power.

To examine this question I will use data from the Renewable Energy Planning Database, which is maintained by DESNZ itself. This contains records on almost every renewable energy project of at least 175 kW for which planning permission has been applied for since the mid-1990s. Some of the records are incomplete but the data is good enough to provide a reliable picture of the development status of utility-scale projects, which I will assume to be those with a planned capacity of at least 5 MW and with at least 2 wind turbines for proposed wind farms.

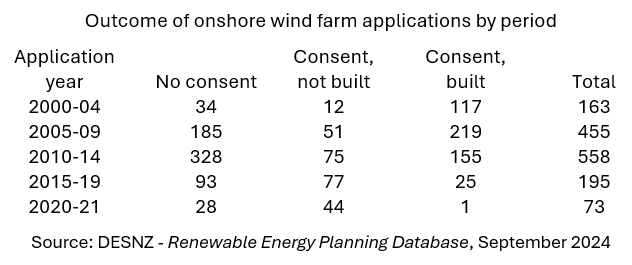

The database contains records of 1,563 proposed wind farms for which planning applications have been recorded. The outcomes of these planning applications are shown in the table above. I have omitted projects for which applications were submitted in 2022 onwards. In many cases the final planning decision has not been made, and even for those which have been given planning consent there has not been sufficient time to decide whether or not to proceed with construction. Projects are classified as having been built if their development status is recorded as (a) under construction, (b) operational, or (c) decommissioned.

The figures show that the majority of applications receive planning consent, though in some cases the process may be slow or may involve modifications to the original proposal. The overall success rate is 54%. The one period in which a majority of applications did not receive planning consent was 2010-14 for which the refusal rate was 58%. There was a high level of applications during this period with developers seeking to take advantage of generous subsidies under the Renewables Obligation scheme, so the high rate of failed applications may reflect poorly designed projects which were either withdrawn or refused.

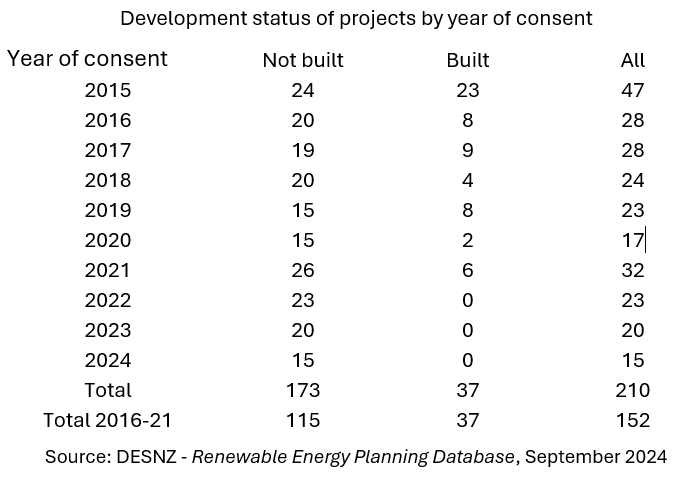

The table above provides more details on whether projects with planning consent granted in the last decade get building organised by year in which the planning consent was granted. Only 25% of the projects consented in the years from 2016 to 2021 had been built or started construction by the end of September 2024. There was an abrupt change after 2015. Most likely, the reason for the change was the closure of the Renewables Obligation scheme in 2017 for new wind farms. It is now harder for new projects to obtain subsidies and the effective offtake prices which they can earn are substantially lower than for projects that earn ROCs. Put harshly, the regime for supporting onshore wind has become much less generous than up to 2017.

The total capacity of onshore wind projects that received planning consent from 2015 to 2024 but have not yet been built is 7.9 GW, of which 7.0 GW is in projects located in Scotland.

The idea, propagated by both DESNZ and renewables lobbyists, that the development has been stymied by delays and objections in the planning system is simple nonsense. The truth is that developers have chosen not to build projects that have planning consent. One possible reason is that they hope that the subsidies which they receive will become more generous in future. A related reason is that developers have adopted a strategy of accumulating portfolios of consented projects, from which they can choose which ones and when to develop.

Overall, the announcement by DESNZ about changes to planning arrangements for large onshore wind farms in England is just a charade. It is accompanied by crocodile tears about planning delays and supposedly NIMBY objections. The Renewable Energy Planning Database shows an entirely different picture of developers who are gaming the system in the hope that they can persuade foolish policymakers to give them larger subsidies.

Great article it should be essential reading for any journalist who wants to comment on this matter in a constructive way and hopefully your in contact with a few. I have been wondering myself how on earth Millbrain believes he can get to his 2030 NZ goal, well the 95% version, with how long it takes to translate decisions into intermittent electricity production but hadn't realised how many "shovel ready" projects are still parked. My real concern though is the triumvirate of Miilbrain, Starkie and Sly read this and realise their plans aren't going to deliver and double down again on the pursuit of this daft goal that will generate neither UK jobs nor lower energy costs.

A really interesting article, thank you for the analysis and sharing. I would be interested in your thoughts on the situation in Wales