Will Net Zero reduce electricity costs in 2030?

Background: This piece is an experiment in trying to make the results of quasi-academic research available to a wider audience. I have spent much of the last three months developing and applying a model of UK electricity generation to analyse the implications of the current UK government’s Clean Power goals for 2030 and beyond. In the past, such work would fall between conventional publishing routes in economics. It is too specific and time-sensitive for academic journals which tend to have long lead times. Equally, it is too long and detailed for most policy think-tanks that must worry about core messages and press releases.

The main article below presents the study and summarises its conclusions. It is quite long - nearly 4,500 words - but it is not intended as a detailed description of the model itself. Much fuller information is provided in a Technical Appendix that can be downloaded via a link at the end of the article. Another reason for avoiding conventional academic forms of publishing is a desire to avoid the requirement to provide large numbers of (often marginal) citations. I have provided essential links but no more.[1]

If you find the article interesting, let me encourage you to do two things. First, post comments and questions. I try to respond to most comments on this Substack, unless no response seems needed. Second, circulate a link to the article to friends and anyone you think might be interested. Subscribing to CloudWisdom is free (as I have no interest in earning an income from it) but every writer wants an audience - usually the bigger the audience, the better.

Some readers may disagree with my analysis or conclusions, but the value of publishing this type of work is to promote a wider discussion of policies in an area that is often treated as being for specialists only. Please post comments to explain the reasons for your disagreement. That way we can all benefit from discussion of issues that, in many cases, are neither simple nor unambiguous. At the same time, please be civil in your comments!

Any reader wishing to contact me concerning material in the Technical Appendix should send an email to: cloudwisdom@substack.com.

…..

In defending its policies to decarbonise the UK’s electricity system the current UK government has relied primarily on two claims. The first is that Net Zero will reduce the exposure of British electricity users to variations in gas prices, which they argue are the primary determinant of market electricity prices. The second claim is that, as a direct consequence of reducing the system’s dependence on gas generation, average electricity bills will fall by a significant amount – between 10% and 20%.

This study examines both claims, drawing upon a detailed dispatch model for the GB electricity system. The model has been calibrated using generating and market data for the decade from 2015 to 2024. It has been extrapolated to 2030 under two scenarios: (a) the electricity system as it was in 2024, and (b) the electricity system described in National Energy System Operator’s (NESO) Clean Power 2030 (CP30) study. The model takes account of the correlated random variations in weather conditions, exports and imports, and total demand over the 8-year period from 2017 to 2024. Further technical details of the analysis are given in the Technical Appendix which can be downloaded via the link below.

Dependence on gas prices

The first of the Government’s claims is unambiguously wrong. It reflects the extent to which policymakers get trapped by conventional wisdom and fail to understand changes in the way in which markets function. The claim may have been true a decade ago, but it has certainly not been true for the last five years. There is extremely strong statistical evidence that the primary determinants of market prices in Britain are (a) the level of net imports, and (b) market prices in Germany and France.

The higher are imports the higher are market prices. An increase in imports of 1 GW will increase the average market price in Britain by about £4 per MW. Since the average level of net imports in 2024 was 3.8 GW, that element accounted for a little over £15 per MWh out of an average market price of £73 per MWh. The average market price in Germany (£66 per MWh) was only slightly lower than in Britain. An increase in German prices of £10 per MWh adds about £3.70 to British prices. Electricity market prices are lower in France (an average of £48 per MWh in 2024). Their impact on British market prices is weaker – an increase of £3.10 for each £10 per MWh increase in the French market prices.

It might be argued that higher gas prices in Europe push up electricity market prices in Germany and France. Any such effect would be weak. In 2024, gas accounted for less than 15% of electricity generation in Germany and less than 5% in France.

The key point is that the Secretary of State for the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) does not appear to understand the first half of his department’s title. Over the last decade, the British electricity market has come to rely increasingly on imports of electricity. In 2024 Britain was a net importer of electricity in 91% of hours in the year. Few would suggest that the British market’s reliance on imports will fall over the next five years. Indeed, plans to build more interconnectors imply that the average level and hours of imports are likely to increase. That, on its own, will mean that British market prices are more likely to increase than to decrease.

While the commitment to decarbonise the electricity system is an additional element, the current government’s policies reflect an obsession with exposure to world gas prices that goes back nearly two decades. In the mid-2000s the UK ceased to be self-sufficient in natural gas. Over time it came to rely increasingly on imports from Norway by direct pipelines, from Russia via North-West Europe, and LNG from the Middle East.

This change had two crucial consequences. First, there was a one-off increase in UK gas prices as the market switched from export parity (European prices minus transport costs) to import parity (European prices plus transport costs). Second, and very unfortunately, this switch from export to import parity prices coincided with a cyclical increase in gas prices from 2004 to 2008. The lesson that policymakers drew from this episode was that real gas prices would increase in the medium and long term. Hence, ever since the mid-2000s, the broad goal of British energy policy has been to reduce the country’s reliance on gas.

The way of achieving this goal has been to use capital-intensive forms of electricity generation – nuclear power and renewables – in place of the direct or indirect use of stored energy in the form of fossil fuels. The justifications offered for this strategy have changed with the intellectual climate - from arguments about ‘peak’ oil and gas to emissions of greenhouse gases – but the common thread has been a conviction that gas prices will ‘always’ increase in future.

Figure 1

Source: World Bank – Annual Commodity PricesThe current Secretary of State may be entirely sincere in his belief in the importance of Net Zero. However, the reality is that this is a veneer on the longstanding position of those responsible for UK energy policy, namely that gas will always become more expensive. Figure 1, which shows real gas prices for the quarter century since 2000, does not provide much support for this position. In each region, real gas prices have experienced occasional sharp spikes but have tended to revert to either a constant or declining mean trend. The belief that real gas prices will remain consistently high or even increase substantially over time is patently wrong.

An unstated assumption in the official story of the relationship between electricity and gas prices is that the ratio of the two is relatively stable. As Figure 2 shows that is not true. The ratio between the market power price and the market gas price has varied from 2.17 to 4.12 over the 12 years from 2013 to 2024. The ratio tends to be relatively high when the gas price is relatively low, but the correlation is not especially strong. Further, the average ratio for the period 2013 to 2018 was 2.76, considerably lower than the average of 3.15 for 2019 to 2024 when the share of renewable energy in total generation was considerably larger than in the earlier period.

Figure 2

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from Nordpool and National GasWhile it is convenient to blame the spike in gas prices for the very high prices in 2022, most commentators fail to point out that average net imports fell from 2.8 GW in 2021 to -0.5 GW (i.e. net exports) in 2022 before recovering to 2.7 GW in 2023. The major, though not the only, factor behind the large switch from net imports to net exports in 2022 was a reduction in French nuclear output, when plants had to be shut down for emergency repairs. This pushed up the wholesale prices of electricity very sharply throughout north-west Europe, an outcome that was exacerbated by a reliance on gas generation as the substitute for French nuclear power. Any benefit from the lower reliance on imports in the British market was greatly outweighed by the increase in German and French market prices.

Governments over the last two decades, including the one in which Ed Miliband was previously Secretary of State for the same department, have chosen to increase the UK’s reliance on electricity imports. That strategy has many advantages, but the government cannot escape responsibility for its direct consequences.

Will electricity bills fall?

To bolster the argument that Net Zero will reduce dependence on gas prices, its advocates have claimed that renewable energy is ‘cheap’ and will, therefore, lower the costs of electricity generation in the medium and longer term. Since solar and wind plants have until recently received large subsidies via various mechanisms, the claimed low cost of renewable generation refers to what may happen in future rather than what has been the case up to now. Again, there is heavy reliance on the idea that 2022 sets the baseline for future gas prices.

Two kinds of evidence are cited to support the assertion that renewable electricity generation is relatively cheap. One is that estimates of levelised costs for new solar and wind plants suggest that their costs per MWh of output are lower than the levelised cost of generation from gas plants (CCGTs). The problem is that such estimates rely heavily on invented assumptions for projects that will commence in 2030 or 2040 rather than actual data for recently completed plants.[2]

The second type of evidence is the outcome of auctions for subsidised generation from renewable plants. Some of these auctions suggested that developers were prepared to build new plants at offtake prices either below or close to prevailing market prices. Subsequently, there has been ample evidence of what economists call ‘the winner’s curse’. Successful bidders and their suppliers have reported large write-downs because they mispriced their bids. In addition, low auction prices do not allow for the system costs of managing intermittent supplies. Thus, comparing auction prices with the cost of operating, say, gas plants is a classic category error – a case of comparing apples and oranges.

Modelling system generation

To assess the claim that Net Zero will lower electricity bills it is necessary to examine the full system costs with different generation mixes under a wide range of conditions that affect both supply and demand. This is difficult: even compiling reliable estimates of current generation costs requires a lot of work. As authors from Mark Twain to Niels Bohr have pointed out, prediction is difficult – especially about the future.

A crucial issue is how to capture the impact of variations in weather. For this assessment I have used half-hourly data on demand and generation by type from 2017 to 2024. The data have been scaled to match NESO’s assumption of an increase in total demand of 11% in 2030 relative to 2023, together with NESO’s assumptions about growth in generating capacity for renewable generators up to 2030. These and other assumptions described in the Technical Appendix.

For each period, output from renewable generators and nuclear plants plus net imports is calculated to give base supply. This is adjusted to allow for storage – mainly batteries – which is topped up during periods of (relatively) low demand and run down when demand is high. When demand exceeds base supply, the gap is filled by backup generation. When base supply exceeds demand, the surplus is reduced using a priority list that takes account of variable operating costs, subsidy arrangements and the different situations of plants connected to the grid and distribution network. If there is still a surplus, generators receive compensation for curtailment.

The government has modified its NetZero target for 2030 by accepting that some gas generation will be required to meet total demand and ensure the stability of the electricity system. The suggestion is that total gas generation in 2030 will be no more than 5% of total demand. That estimate appears to be rather optimistic. My analysis suggests that average backup demand, after allowing for battery storage, will be about 14% of total demand with a range from 11% to 20% over the eight years examined.

The requirement for backup generation would be reduced if a much higher level of net imports could be relied upon, but, again, that would be very optimistic. Over the three years from 2021 to 2023, the average level of net imports varied from 2.8 GW in 2021 to -0.5 GW (net exports) in 2022 to 2.7 GW in 2023. The combination of restrictions on French nuclear output and turmoil in other markets of north-west Europe had a very large impact on the British market. This and other experience have shown that the UK cannot rely upon interconnectors to balance a shortfall in domestic generation at a reasonable cost.

The consequence is that in 2030 the system will require more than 50 GW of backup gas or diesel generating capacity to match the reserve margin implied by capacity market contracts for 2024 after allowing for the contribution of battery and other storage. Currently, the system primarily relies for backup generation on a combination of (a) combined cycle gas plants close to retirement, plus (b) small gas and diesel turbines or reciprocating engines.

This arrangement would be both expensive and inefficient in 2030. Hence, I have assumed that backup generation will mainly comprise of modern single cycle gas turbines, which are relatively cheap to build on existing sites and are designed to operate on standby. The previous government recognised that about 30 GW of new gas capacity should be built by 2030. The current government has given no indication of how it will manage this requirement. If little or no new gas capacity is built, then both system generating costs and emissions from power plants will be higher than shown below.

Generating costs in 2030

Using 2024 prices, and averaged over eight years of weather, trade and related variables, the generating cost to meet total demand in 2030 with an electricity system equivalent to the one we have today would be £28.9 billion. That figure includes the value of power at average market prices plus the cost of the Renewables Obligation and Contracts for Differences subsidies, not the cost of Emission Trading Scheme permits (see below). The total is equivalent to about £88 per MWh.

On a like-for-like base, the total generating cost for the NetZero electricity system being promoted by the government for 2030 would be £42.1 billion, which is equivalent to about £128 per MWh. Hence, the original claim by the Secretary of State for the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) that energy bills will fall by at least £300 and the more recent claim by NESO that electricity costs will fall by at least £10 per MWh seem implausible at best.

If the overall cost of meeting electricity demand is to increase by about 45%, the necessary reduction in network charges and other costs would have to be remarkably large for the overall cost of electricity to fall by a significant amount. Yet, for example, National Grid has made public statements to financial markets that it will need to invest up to £50 billion by 2030 to upgrade its transmission system to accommodate the needs of Net Zero. While there may be doubts about the feasibility of spending such large sums over six years, there can be no doubt that such investment will imply a substantial increase in transmission costs. The situation is similar for other transmission and distribution network operators.

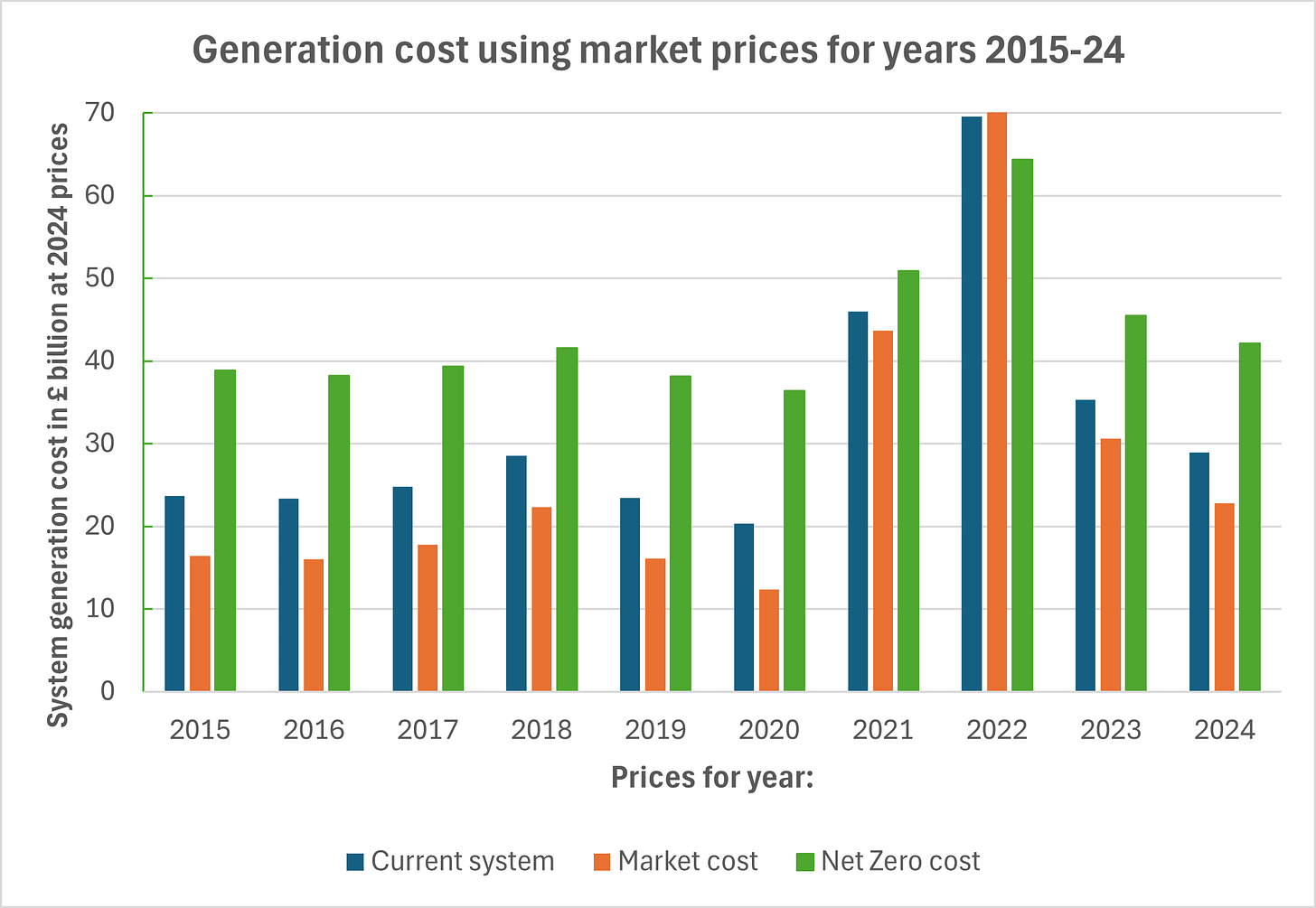

Figure 3Source: Author’s calculations

Even though it is based on a misapprehension, Figure 3 examines the Secretary of State’s argument that the Government’s policies will reduce the UK’s exposure to gas prices. How would that work out using average market prices and gas prices for the decade from 2015 to 2024? The estimates shown in the figure for the pricing year 2015 are calculated by running the analysis for the average wholesale electricity and gas market prices for 2015 converted to 2024 prices. The figure compares:

(a) total generation cost for the current system (blue),

(b) total cost of electricity at the average market price (orange), and

(c) total generation cost for the Net Zero system (green).

In each case, total demand is calibrated to match NESO’s projection for 2030.

In every year except 2022, the Net Zero system has a higher total cost of generation than the current system. Over the decade 2015 to 2024 the average cost of generation under the Net Zero system will be £43.5 billion per year at 2024 prices compared to £32.4 billion under the current system. Equally important, the average cost of generation at market prices over the decade would have been £27.1 billion, even after allowing for the exceptionally high prices in 2022. To insure against one year of very high prices the Secretary of State wants to spend an average of £16.4 billion per year. This translates to an average increase of 55% in the system cost of generation relative to the average wholesale cost of electricity.

The Net Zero system being promoted by current government policies will increase generation costs in nine out of ten years. It would provide a small measure of insurance against the combination of a crisis in the European gas market and closure of many nuclear plants in France, but with the certain consequence of incurring generation costs that are much higher over a decade. This seems like a rather bad bargain.

Reducing carbon emissions

It will be argued that the Net Zero system will reduce carbon emissions, though at a considerable cost and not by as much as claimed. Still, that is not the claim made by the current Government which asserts that its policies will both reduce costs and reduce emissions.

In fact, there is a hidden story here. Subsidies for renewable generation are only a part of green policy mix. For more than 15 years, generators burning gas and other fossil fuels have been required to purchase emission permits either via the EU Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) (subject to a carbon price floor) or via the UK ETS that replaced it in 2021. Converted to GBP per tonne of CO2-equivalent (tCO2) the average permit price rose from £18 (the floor price) in 2015 to about £95 per tCO2 in 2022, though the UK price has fallen substantially since then.

Using a standard emission factor of 0.37 tCO2 per MWh of generation the cost of emission permits added nearly £35 per MWh to the cost of gas generation in 2022. Applying the Secretary of State’s argument, the cost of UK ETS permits pushed up the average market price of electricity from £189 to £224 per MWh in 2022. That added £11.4 billion to the cost of electricity at wholesale prices in Figure 3. The apparent advantage of the Net Zero system in 2022 is the product of emission charges whose cost escalated sharply during a period of extreme stress in the electricity market.[3]

The problem is that EU and UK policies concerning carbon taxes are an economic nonsense. It is correct to argue that there is a case for imposing a tax reflecting the economic cost of the externality caused by CO2 emissions. However, that argument is only correct if there are no other interventions to promote low-carbon generations. This is not the case: both the UK and EU countries are wedded to a huge range of measures designed to favour wind, solar, biomass and other forms of favoured generation.

The result, as we have seen, is an expensive and inefficient structure of interventions in the electricity market which have steadily pushed up the prices of electricity paid by households and businesses. To understand the full impact of measures to promote low carbon generation, we should treat the costs incurred to purchase emission permits on a par with levies and taxes to fund renewable energy.

The average UK ETS permit price in 2024 was £37 per tCO2. According to the plan announced in October 2023 the volume of permits auctioned will fall by about 65% from 2024 to 2030. That is greater than the expected reduction of 45% in total generation from gas and other fossil fuels. Further, the share of gas generation from gas turbines rather than CCGTs will increase so the average emission factor for gas generation is likely to increase from 0.37 tCO2 per MWh by 25%. The net effect will be to greatly increase the share of total permits used by the electricity sector ,from about 40% in 2024 to nearly 85% in 2030. It is inevitable that this will push up the real price of emission permits very sharply, since the demand for gas backup will be price inelastic.

If the UK ETS price rises to match its peak of about £100 per tCO2 in 2022 the system cost of emission permits for electricity generation will at least double from about £1 billion in 2024 to over £2 billion in 2030, both at 2024 prices.

Other system costs

Likewise, the cost of system balancing and capacity market payments will increase sharply up to 2030. As described in the Technical Appendix, I have constructed a statistical model of period-to-period variations in balancing costs. This model suggests that the total cost of system balancing will increase from approximately £3 billion to £7.4 billion in 2030. More than 85% of this cost is directly linked to the share of generation from solar and wind plants.

The final element of the system cost of providing sufficient generation is the cost of capacity payments to ensure that the availability of firm capacity to meet system needs plus an adequate reserve margin. The levy to cover the cost of capacity payments increased from £120 million in 2017 to £1.13 billion in 2024. That cost will continue to rise. The capacity price for 2024 was £22 per kW at 2024 prices. The equivalent price for 2028 was £72 per kW. That was not sufficient to procure the amount of firm capacity that will be required for 2030, as the total requirement will increase by up to 20% while the potential supply is falling rapidly as plants are retired.

Experience of the PJM capacity market in the US indicates that capacity auction prices rise very greatly as the balance between supply and demand switches from excess supply to excess demand. Thus, a conservative estimate is that the total cost of capacity payments in 2030 will increase to about £7.4 billion in 2030 at 2024 prices. That reflects a capacity price in 2030 that is double the price for 2028. In the PJM market the auction capacity price increased nearly tenfold from 2023 to 2024, so such an increase is certainly not outside the bounds of the evidence available.

Summary

Table 1 summarises the results of my analysis. Total generation cost, including ETS permits, capacity payments and system balancing, under the Net Zero system will be £58.9 billion versus a total of £34.1 billion under the current (2024) system. Every element of the total cost will be substantially higher for the Net Zero system. Expressed per unit of total demand, the total generation cost will increase from £104 per MWh to £179 per MWh, an increase of 72%.

The total generation cost only accounts for about one half of electricity bills. Predicting what will happen to the other half, which covers network charges and supplier costs, is very difficult. The reason is that network operators are expected to invest heavily to extend and upgrade both transmission and distribution networks. Ofgem has squeezed the allowed rate of return on capital for networks at recent price reviews. However, operators will not agree to increase their investments, nor will they be able to raise the necessary finance, unless they are allowed a higher real return on capital. In consequence, the big uncertainty concerns how much network charges must rise to fund the investment in electricity networks assumed in the CP30 strategy.

What is certain is that the network and supply component of electricity bills will increase alongside the increase in total generation costs. The only way in which electricity bills will fall is by a sleight of hand, such as transferring energy levies to gas bills or providing budgetary subsidies. Such measures do not reduce any of the costs but merely transfer them to different headings.

Is it true?

Many readers will be inclined to question whether such an increase in generation costs is likely to happen. I should emphasise that I am not making a forecast for actual generating costs in 2030. The figures in the table are my best attempt to compare total generating costs in 2030 under two scenarios that meet 2030 demand: (a) the electricity system as it operated in 2024, and (b) a Net Zero electricity system as described in NESO’s CP30 plan.

Some observers believe that the British energy policies are formulated in a parallel universe, that is at best tangential to the world in which the rest of us live. This universe is one in which the constraints in investment and human resources do not exist. There are no queues for transmission equipment, gas turbines and wind turbines. The main operators of offshore wind farms are not cutting their investment budgets. And so on.

Reading between the lines of bureaucratic-speak, one might infer that NESO itself does not believe in the CP30 strategy, since it relies on various implausible assumptions. Naturally, it is unwilling to speak truth to its political masters, so what we are given is fudge in large quantities.

What the analysis reported here makes clear is that implementing the CP30 strategy will push up total generating costs by a lot, almost certainly by 50% and quite probably by more than 70%. The claim that the CP30 strategy will reduce electricity bills by as much as 20% is simply absurd. As a strategy to reduce the UK’s dependence on gas, it is misconceived and very expensive. There is little more that can be said! Such is the nature of policy in the UK today.

End Notes

[1] I had the good fortune to be tutored at Cambridge by two subsequent winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics - James Meade and James Mirrlees. Both were wonderful people and inspiring teachers. Neither had much time for academic conventions and they tended to address issues from first principles, so they kept their citations to a minimum. They are examples that I am happy to follow.

[2] I have written a study of levelized costs for the National Center for Energy Analytics, which will be published in the spring of 2025.

[3] Sadly, this is a lesson that UK policymakers should have learned from the experience of the California market crisis of 2000-01. In that case the problem was centred on the trading scheme for NOx permits, whose price shot up when hydro generation was severely restricted by a drought. Californian gas plants were unable to operate profitably because of the cost of emission permits, and the system became even more reliant on imports from out-of-state plants. Because of price caps, the outcome was a period of rolling blackouts that caused great disruption to economic activity in California. UK energy policymakers have consistently demonstrated that they are unable to learn important lessons from the rest of the world.

Hi, apart from electricity generation, there is the other commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by 81% by 2035 compared to 1990, made by Keir Starmer at COP29.

From Statistical Review of World Energy 2024, in 1990, U.K. CO2 equivalent emissions from energy, process emissions, methane and flaring were 595 million tonnes. So by 2035 they need to be 113 million tonnes. In 2023 they were 327 million tonnes. So if other GHG sources ( e.g. from farming) are ignored, fossil fuel energy consumption has to be reduced by 65% by 2035 compared to 2023. Now, in 2023, fossil fuels, mostly oil and gas, provided 5.16 exajoules (EJ) of primary energy. If U.K. has to replace 65% of this, it has to find 3.35 EJ of new CO2-free energy. Even if we assume that miraculously U.K. will reduce its primary energy requirement by 40%, it still has to find 2.01 EJ of new CO2-free energy. This is equivalent to providing 65 GW of continuous CO2-free energy or around 22 new Hinckley Point C nuclear power plants or 145 GW of new wind assuming a very optimistic capacity factor, CF of 0.45. For refernce, CF for wind currently is 0.31(for solar it is 0.11) and installed wind capacity is around 31 GW. So almost everything has to be run on CO2-free electricity There also has to be a massive change in lifestyle on top of the 40% reduction in primary energy consumption assumed - enormous reductions, almost to zero, in meat and dairy consumption, aviation , cement and steel industries . …

All this will be impossible to achieve in the real world by 2035. Anyway, what would be the cost of all this if it were possible?

This is a tremendous piece of work. I know just how much effort is required to pull something like this together having done various analyses myself. So well done.

It underscores the idea that the markets have changed how they operate and backs it with hard analysis, as well as showing that the Miliband plan is in reality a high cost option. I think it's possible to discern many of your findings when closely looking at a chart of electricity supply by source with a price overlay like this one:

https://i0.wp.com/wattsupwiththat.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Generation-jan-2023-1722888879.3157.png

I have yet to complete my analysis of 2024 because of the need for data cleaning which can be very time consuming. However, it is easy to see that intraday price volatility is huge, particularly when there is a high share of renewables on the system. When it is windy there are huge swings in interconnector supply between net export and large imports, and pumped storage also plays a role. Back then batteries were small beer, and only reported for net discharge AFAICS under the OTHER categroy of generation. Downloading individual metered readings for batteries only shows the net charge or discharge over a settlement period, not the total input for charging/cooling and discharge output, so it is hard to get good information on battery performance, and unfortunately Bess Analytics has now disappeared behind a paywall having been acquired by Cornwall Insight, so now we depend on commentary from the like of ModoEnergy for analysis (they are very good though).

If we rearrange the data in price order we get a chart like this

https://i0.wp.com/wattsupwiththat.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Gen-by-Price-Jan-2023-1716328267.549.png

which shows clearly that when wind output dominates prices are set by competition between wind sources, and tend close to zero or negative when we have a surplus export. Subsidising exports for the benefit of foreign consumers has never made sense to me. As capacity increases we will see more hours with wind surpluses and the surpluses will grow in low demand hours. It is clear that the structure of the market will concentrate curtailment on those wind farms that get no compensation when prices are negative. We can see this already with Seagreen and Moray East, which have yet to take up CFDs and become the dominant volumes of curtailment. The price they have been getting has been steadily reducing too, as more competition starts to come on stream from other wind farms in construction which also get no subsidy protection.

Incidentally, I think you are incorrect about ROCs in your Annex. For now they remain traded, although the market is very opaque and not openly reported unless you subscribe to a specialist price reporter like ICIS. However, the final recycle value of ROCs that includes the premium for redistribution of the cashout fund is published (often obscurely) by OFGEM. REF has a convenient table of the history at the bottom of the page here:

https://www.ref.org.uk/energy-data/notes-on-the-renewable-obligation

I am using an assumption of a 12% premium for the current year, giving a value of £72.50/ROC, as a guess that allows for slightly disappointing actual output from renewables and probably more stable demand. Up for consultation is a proposal to fix the ROC value without trading at a 10% uplift to the indexed cashout value for the life of the scheme between 2027 and 2037 when it expires, because it is anticipated that the balance between the obligation and supply could become much more volatile in future.