Geography and electricity markets Part 3

Most commentaries on the functioning of electricity markets focus on the author’s home country. While that may be instructive if the goal is to contribute to domestic policy debates, such a focus limits the lessons that can be learned from broader comparisons. In previous articles in this occasional series I examined the relationship between electricity prices in countries that are (more or less) directly linked to the UK. In this article I present a broader comparison of medium and large European electricity markets from the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland in Central Europe to Portugal and Great Britain in the West.[1][2]

All countries in this region have implemented policies to promote greater use of renewable generation. In practice, this translates to supporting intermittent generation from solar and wind as opportunities for increasing generation from hydro and biomass are very limited. The trend rate of growth in the share of total domestic load supplied by solar and wind power varies from 2.4 percentage points per year in Denmark, Spain and Sweden to less than 1 percentage point per year for the Czech Republic (0.3), Italy (0.7) and Switzerland (0.9).[3] For 15 countries the median growth rate was 1.8 percentage points per year.

In 2025 the share of intermittent generation as a portion of total load varied greatly across countries – from highs of 60% in Denmark and 44% in Germany to lows of 9% in Switzerland and the Czech Republic. The GB market has moved from a little above the median share of intermittent generation in total load in 2015 to well above the median share in 2025 at 36%.

As one might expect, there is a negative correlation between growth in intermittent generation and growth in dispatchable generation. In the long run, this association has a crucial impact on the difficulty and costs of ensuring reliable electricity supplies. As intermittent sources of generation become more important in total supply, the system operator must find ways of ensuring that there are sufficient backup supplies either (a) on standby to cope with short term fluctuations in intermittent generation, or (b) that can be called upon with 8 to 24 hours’ notice to cover larger but (hopefully) more predictable variations in intermittent generation.

In most countries the share of dispatchable generation in total load has fallen as the share of intermittent generation has risen. The GB market stands out as having moved from a share of dispatchable generation in 2015 (71%) equal to the median value to well below the median share in 2025 (45%). It is moving in the direction of Denmark (20%) and Germany (48%) in being highly exposed to the issues that can arise in any electricity market with a high reliance on intermittent generation and low availability of dispatchable generation.

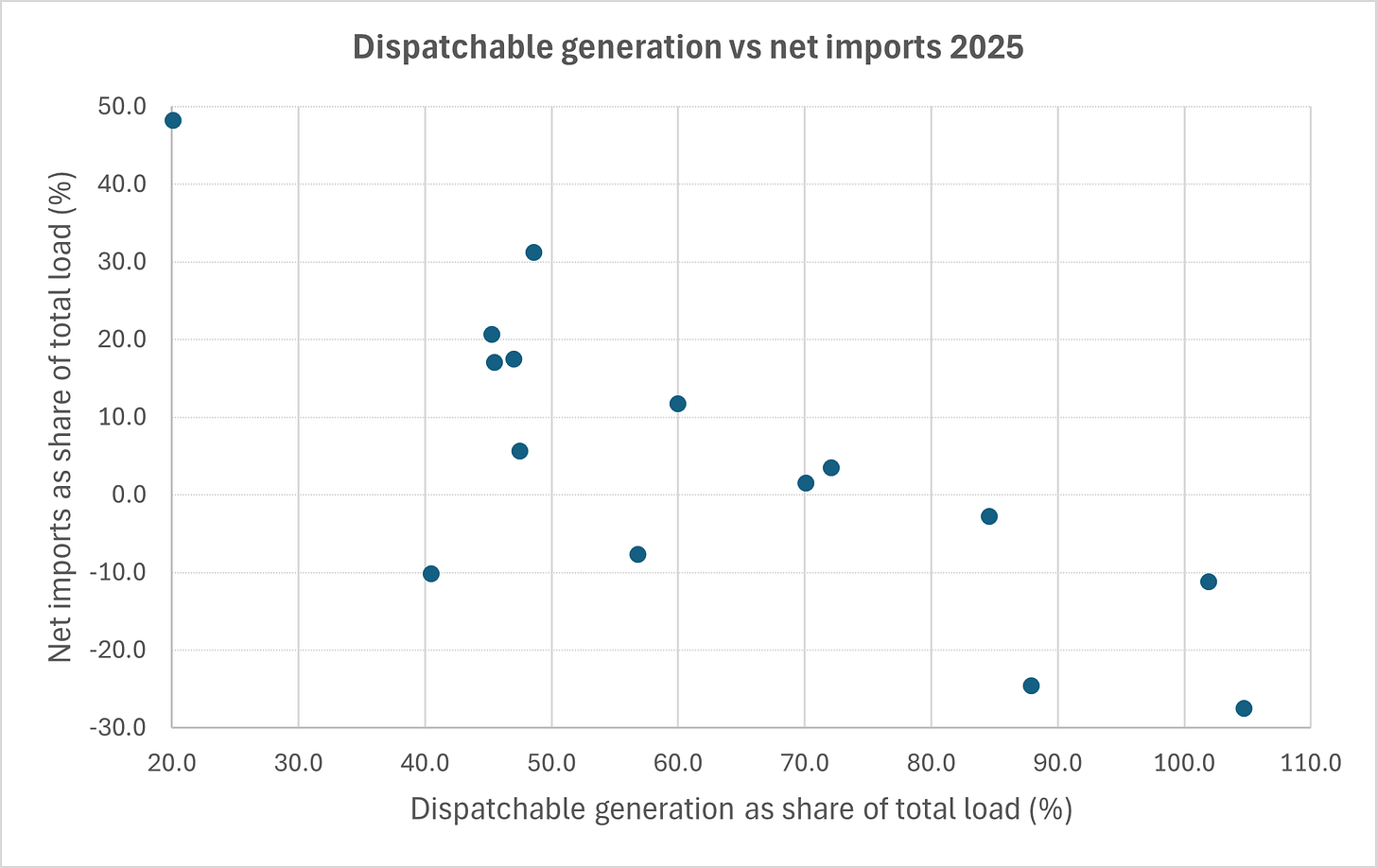

The reduction in the share of dispatchable generation for the GB market has been matched by a large increase in reliance on imports. The GB market’s level of net imports as a % of total load increased from 7% in 2015 – close to the median value of 5% - to 20% in 2025, whereas the median value fell to 3% for the full sample of countries. The share of net imports relative to total load varied greatly across countries in 2025 - from highs of 48% for Denmark and 31% for Portugal to lows of -28% for France and -25% for Sweden (both countries being large net exporters of electricity).

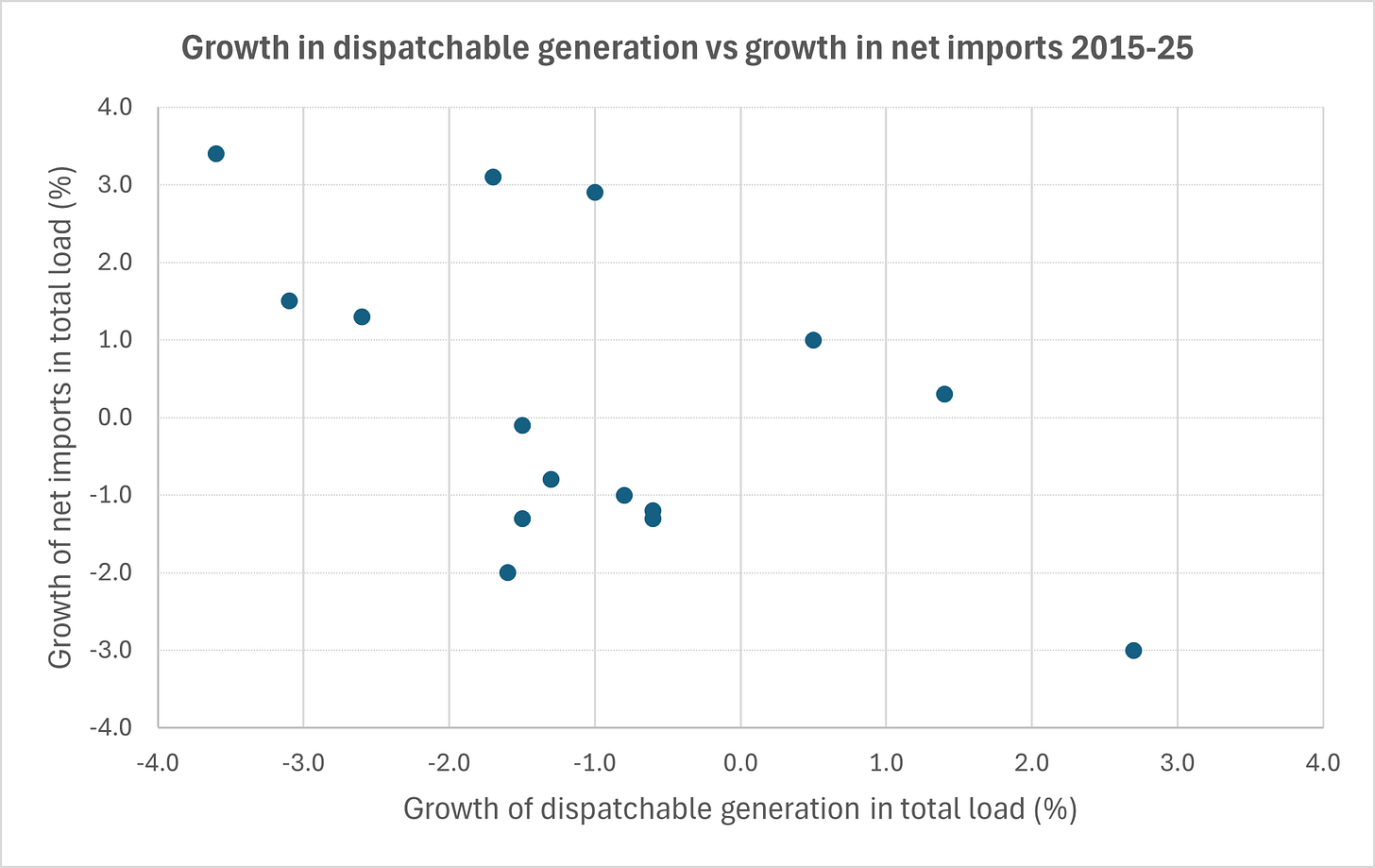

Figure 1

Figure 2

The strongest correlations in the cross-country database concern the relationship between the share of dispatchable generation in total load in 2025 and the share of imports in total load. Figure 1 above shows that the lower (more negative) the growth in the share of dispatchable generation from 2015 to 2025 the higher was the increase in the share of net imports over the same period. Figure 2 shows the same relationship in 2025 levels with an even stronger negative correlation (-0.79).

The inference is simple and important: the higher the share of dispatchable generation in total load the lower the reliance on imports to meet total load or the higher the level of exports. That is true for both levels and growth rates. This matters because there is a delusion among policymakers in the UK that somehow the variability of output from intermittent renewable generation can be offset by exports when such generation is high and imports when it is low. That is a recipe for an unstable generation system with large fluctuations in prices between periods when renewable output is high – and, thus, power must be exported usually at low prices – and periods when renewable output is low and market prices are high.

Setting aside self-interested dogma, nobody can question that the country with the most reliable electricity system in West and Central Europe is France. Other countries might not choose to have the level of generation capacity that leads to consistent exports, but they are dependent on the service provided by the French electricity system in balancing supply and demand in the region. Sweden and Norway play a similar role for NW Europe, though at the cost of increasing domestic debate in Norway about the impact of exports on market prices. In the 2010s the Czech Republic was a large net exporter to Central Europe, but that role has decreased in recent years.

From 2015 to 2025 the median value of country average market prices increased by 2.2 times from €40.1 per MWh to 89.3 per MWh but the dispersion of market prices relative to the median fell slightly. The average GB market price (€56 per MWh) was the highest of all 15 countries in 2015 but increased up to 2025 by less than the average market prices in many other countries so it was only 7% higher than the country median in 2025. Two countries that moved down the ranking of average market prices relative to the country median were Spain and Portugal which fell markedly over the period, being about 25% above the country median in 2015 but slightly more than 25% below the country median in 2025.

France and Denmark switched places in the ranking with France being close to the country median in 2015, while Denmark was 40% below the country median. By 2025 France had fallen to 68% of the country median while Denmark had risen to just below the country median. Such shifts may be politically very sensitive, because they mitigate or exacerbate the general increase in market prices that occurred over the decade. In Central Europe, Austria, Czech Republic, and Hungary all moved up the ranking markedly.

Finally, despite the rhetoric the correlations between the increase in average market prices over 2015-25, and (a) the increase in the share of intermittent renewables over 2015-25, or (b) the 2025 level of the share of the intermittent renewables are both very close to zero. The frequent claim that promoting the development of intermittent renewables will reduce market prices or slow their increase is not supported by any of the evidence from these cross-country comparisons. Remember, too, that these figures relate solely to prices in wholesale markets, so that they take no account of the levies that are required to fund subsidies for renewable generation as well as to extend transmission grids to serve generators that are more geographically dispersed.

No matter what the merits of wind and solar may be in reducing the level of CO2 emissions, strictly from the perspective of operating electricity systems, policies to promote them lead to a reduction in demand and revenues for dispatchable generation and thus to an increase in reliance on imports. There is, so far, little cross-country evidence that large investments in storage can alter that trade-off.

If the goal is to ensure reliable system operation with a high level of self-sufficiency while reducing CO2 emissions, the cross-country experience suggests that we should adopt the patterns of generation in countries such as France and Sweden. These rely primarily on generation from nuclear plants and reservoir hydro. Unfortunately, for many green movements, nuclear plants and dams are as or more sinful than fossil fuels.

Since opportunities to develop new hydro capacity are very limited in most European countries, the choice is between opting for nuclear power on a large scale or accepting lower levels of reliability if the green veto on nuclear power is not challenged. In the latter scenario, lack of resilience in a large country such as Germany will spill over to its neighbours unless those neighbours are willing, in extreme conditions, to isolate the source of instability to prevent local failures spreading beyond system boundaries.

For example, the major breakdown in Spain in April 2025 caused the collapse of the closely integrated electricity system in Portugal but not in France and North Africa, because the interconnectors were shut down as a by-product of the domestic failure in Spain. The experience was similar for the major system failure in Texas in February 2021. Large electricity systems that rely heavily on imports such as GB, Italy, and Germany need to think hard about how they should respond to system failures in neighbouring countries.

Since Germany is so central to the web of import/export links in Western Europe, other countries in the region ought to be having nightmares about the potential consequences of a Spanish-style failure in Germany. Instead, as is all too often the case in Europe, there is an overwhelming sense of complacency that nothing too bad will ever happen.

[1] I have omitted Ireland because the data available on the Irish Single Electricity Market is erratic, while Ireland’s population falls below the threshold of 6 million that I chose to limit the sample. I have also excluded countries in SE and NE Europe on grounds of either size or special circumstances. Finally, Norway has a population of less than 6 million, but it is also an extreme outlier in the characteristics of its electricity market because of its primary reliance on hydro power for generation.

[2] Most of the data used in this article, including imports and exports of electricity, has been extracted from the Transparency Platform maintained by ENTSO-E – the organisation of European transmission system operators. National Grid ESO (now NESO) stopped submitting information for the GB market to ENTSO-E in 2021, so I have used equivalent data compiled and reported by Elexon for the years from 2021 onwards. The ENTSO-E Transparency Platform started collecting data from mid-December 2014, so I have adopted a data period from January 2015 to November 2025.

[3] To be clear, these growth rates mean that the “normal” share of intermittent renewables in total domestic load increased by 24 percentage points in Denmark from 2015 to 2025, but only by 3 percentage points in the Czech Republic over that period. The trend growth rates were estimated using a linear regression with the % share of intermittent renewables as the dependent variable with month and years since 2015 as the independent variables.

Thank you Gordon: as ever the model of clarity.

In his book 'Going Nuclear: How the Atom Will Save the World and Build a Sustainable Future', which I enjoyed reading, Tim Gregory robustly attacks the arguments of those "environmentalists" who insist on energy future built solely on wind and solar, pointing out such an approach is in practice doomed to continue reliance on fossil fuels due to the well-known flaw of relying on the weather, if not here, then "somewhere else" where the sun must be shining and the wind blowing.

There now seems daily opportunity to read lurid stories of Russian aggression, forthcoming wars, and our vulnerability, most of which I ignore, but indeed, reliance on sub-sea inter-connectors isn't looking too clever as a strategy.

Finally, and purely for amusement: during a brief and pointless argument with my sister-in-law, I was met with "I've worked in the nuclear industry and nuclear waste is a big problem". I might have been impressed but for the fact that she has a geography degree, limited technical knowledge, and is a librarian. Tim Gregory argues that a significant proportion of "waste" is still very energy-dense and should be regarded instead as fuel for future reactors.

Thank God for France and Norway.

Yet another example of our reliance on ‘the kindness of strangers’?