Developing solar, bioenergy and storage projects

In my last article I examined planning and development decisions for onshore wind farms to assess DESNZ’s belief that changes in planning procedures would accelerate the construction of new wind farms. However, onshore wind farms only account for a diminishing share of renewable energy projects for which planning applications are submitted. From 2010 to 2014 onshore projects accounted for about one-third of all renewable energy planning applications. That share has fallen to just above 10% in the period from 2020 to 2024.

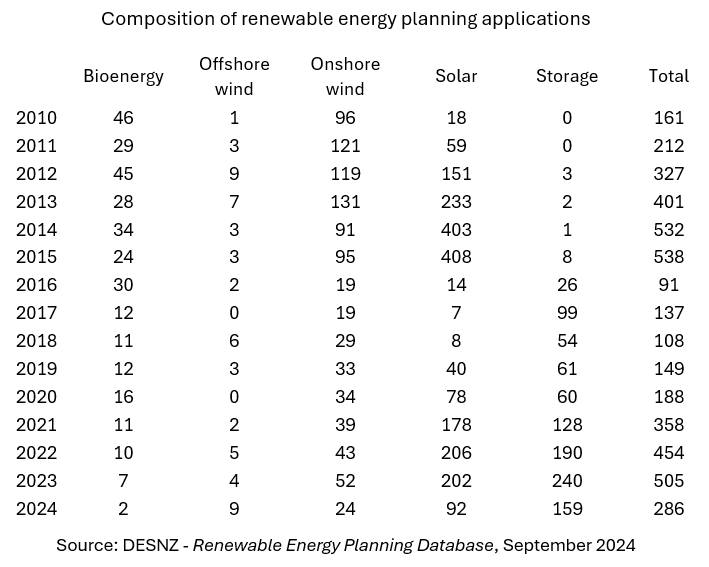

The table shows the distribution of applications by broad categories. Bioenergy is a mixed bag including anaerobic digestion and landfill gas plus energy from waste and biomass combustion. Storage consists largely of battery projects but includes compressed air and pumped hydro. All of these projects are for utility-scale use, i.e. a minimum of 5 MW of either generation capacity or supply.

The figures show a surge in applications for solar projects from 2012 to 2015 due to the generosity of the subsidies available under the Renewables Obligation. Since 2020 the numbers of solar and battery projects have grown substantially. Often these are combined but there are many standalone solar and battery projects. On the other hand, the number of bioenergy projects has declined sharply since the early 2010s and there is little prospect that will change.

The figures also refute the suggestion that the claimed “ban” on onshore wind projects in England was the reason for the decline in the development of new onshore wind farms in the UK. In reality, the reduction in generous subsidies under the Renewables Obligation discouraged the submission of solar projects by even more than onshore wind projects. The slump and later recovery in the number of solar projects reflects assumptions about whether such projects can obtain guaranteed sales agreements at above-market prices, either via corporate power purchase agreements (PPAs) and/or contracts for differences (CfDs).

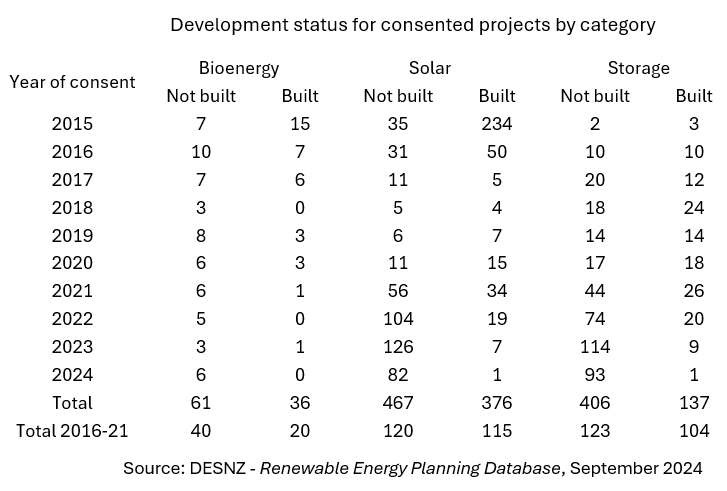

The table above extends the analysis of whether renewable energy projects with planning consent are built or remain inactive. As for onshore wind, a large majority of bioenergy and solar projects which received consent up to 2015 were built. That pattern has changed from 2016 onwards, though to different degrees. One-third of bioenergy projects that received consent from 2016 to 2021 have been built. That share is nearly 50% for solar project and a bit lower for storage projects.

Comparing the figures for different project types, onshore wind projects stand out as having a particularly low chance of being built. This might reflect constraints on network capacity in Scotland where most of the onshore wind projects are located.

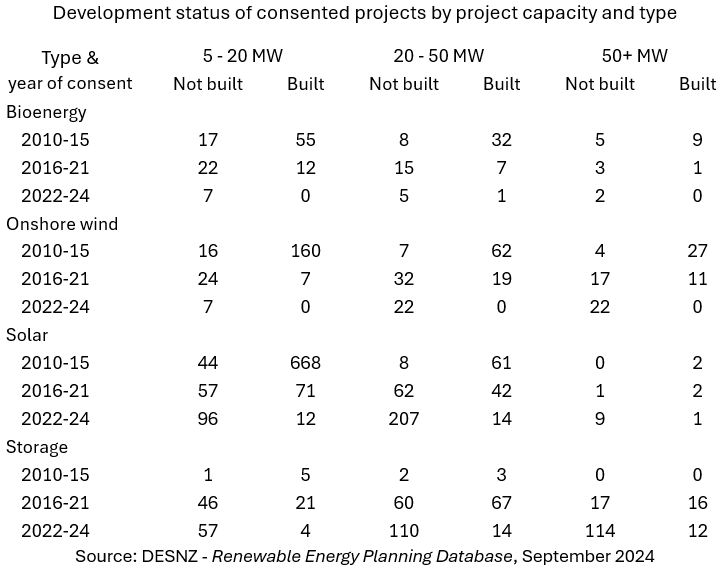

Another question that may occur is whether the probability that a project will be built depends on its size as measured by its total capacity. The table shows that for all project types the large majority of those consented from 2010 to 2015 were likely to be built. That changed for the period from 2016 to 2021 but to differing degrees by project size and type. For onshore wind, medium and large projects were somewhat more likely to be built than small projects. The proportion of consented projects that were built was 38% for projects of 20+ MW but only 23% for projects of less than 20 MW. This pattern was reversed for solar projects. The majority (55%) of consented projects of less than 20 MW were built, but only 40% of project of 20+ MW. For storage, small projects were less likely to be built but large ones were more likely to be built.

Overall, since 2016 there has been considerable variation by project type and size. There appears to be no consistent patterns that would suggest, for example, difficulties in obtaining grid connections or sources of finance are the primary reason for projects not being built. In large part there may a lot of idiosyncratic factors that account for these decisions.

We know that the grid does not have the capacity to handle all of the onshore wind and other renewable energy projects that have been given planning consent in Scotland. Even setting that aside, it seems fairly clear that renewable energy developers have been deliberately building up portfolios of consented projects that they may never build, except perhaps under the most favourable conditions.

Policy on grid access has been connect & manage the constraints but given the sheer weight of connections that have been required the supply chain and the DNO's have been swamped to keep up. NESO Connections Reform project outcome will see a total reset now im surmising.